At St. Jude's our worship is shaped by scripture, tradition, and reason.

|

|

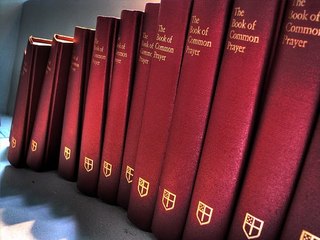

In the Episcopal Church it is often said that "praying shapes believing." Worship is central to the life of our church. Worship is designed using the rich treasury of resources contained in The Book of Common Prayer and the Hymnal. Through prayer and song we seek to glorify God, through Jesus Christ, in the power of the Holy Spirit.

Episcopalians worship in many different styles, ranging from very formal, ancient, and multi-sensory rites with lots of singing, music, fancy clothes (called vestments), and incense, to informal services with contemporary music. Yet all worship in the Episcopal Church is essentially the same, and has its roots in the prayers of the earliest Christians. The Sunday service described in the Acts of the Apostles has continued among many different Christian traditions, including our own. The particular words and prayers used in our church are set down in The Book of Common Prayer. Worship in the Episcopal Church is said to be “liturgical,” meaning that the congregation follows service forms and prays from texts that don’t change greatly from week to week during a season of the year. This sameness from week to week gives worship a rhythm that becomes comforting and familiar to the worshipers. For the first-time visitor, liturgy may be exhilarating… or confusing. Services may involve standing, sitting, kneeling, sung or spoken responses, and other participatory elements that may provide a challenge for the first-time visitor. However, liturgical worship can be compared with a dance: once you learn the steps, you come to appreciate the rhythm, and it becomes satisfying to dance, again and again, as the music changes. In spite of the diversity of worship styles in the Episcopal Church, Holy Eucharist always has the same components and the same shape. We begin by praising God through song and prayer, and then listen to as many as four readings from the Bible. We read through the Bible using a system called a lectionary. The lectionary usually includes a reading from the Old Testament, a Psalm, something from the Epistles, and (always) a reading from the Gospels, read in the middle of the congregation. The psalm is usually sung or recited by the congregation. Next, a sermon interpreting the readings appointed for the day is preached. The congregation then recites the Nicene Creed, written in the fourth century and the Church’s statement of what we trust in. Next, the congregation prays together—for the Church, the world, and those in need. We pray for the sick, thank God for all the good things in our lives, and finally, we pray for the dead. The presider (e.g. priest, bishop, lay minister) concludes with a prayer that gathers the petitions into a communal offering of intercession. In certain seasons of the Church year, the congregation formally confesses their sins before God and one another. This is a corporate statement of what we have done and what we have left undone, followed by a pronouncement of absolution. In pronouncing absolution, the presider assures the congregation that God is always ready to forgive our sins.The congregation then greets one another with a sign of peace. The priest stands at the altar, which has been set with a cup of wine and a plate of bread, raises his or her hands, and greets the congregation again, saying “The Lord be With You.” Now begins the Eucharistic Prayer, in which we hear the story of our faith, from the beginning of Creation, through the choosing of Israel to be God’s people, through our continual turning away from God, and God’s calling us to return. Next, the presider tells the story of the coming of Jesus Christ, and about the night before his death, on which he instituted the Eucharistic meal (communion) as a continual remembrance of him. The presider blesses the bread and wine, and we recite the Lord’s Prayer. Finally, the presider breaks the bread and offers it to the congregation, as the “gifts of God for the people of God.” All Christians—no matter what age or denomination—are welcome to “receive communion.” Episcopalians invite all people to receive, not because we take the Eucharist lightly, but because we take our baptism so seriously. Visitors who are not Christians are welcome to come forward during the Communion to receive a blessing from the presider. At the end of the Eucharist, the congregation prays once more in thanksgiving, and then is dismissed to continue the life of service to God and to the world. Of course, each service is followed by fellowship in St. Jude's Parish Hall. Jokingly referred to as the "Eighth Sacrament," Coffee Hour fellowships enable us to share coffee and "goodies" and catch up on what is going on in the lives of our fellow Episcopalians. |

ScriptureThe Bible is like a small library containing a vast array of material. In the Hebrew Scriptures there are thirty-nine books with the story of creation, the histories, ritual, poetry, songs, wisdom, and prophets of the people of Israel.

Given a piece of scripture’s historical context, how do we translate that context and meaning in today’s world?” The saying “sola scriptura” (Latin meaning “by scripture alone”), is not part of the Anglican way. The Church reads scripture through the lenses of the Fathers and Mothers of our faith and the gift of reason. |

ReasonReason is the knowledge and wisdom that God gives us to help us better understand his will for us as his people. Reason, guided by the Holy Spirit, should always direct the people of God to what is true, just, fair and sensible. As Lewis Garnesworthy, a former Archbishop of Toronto, used to like to say, “To become an Anglican doesn’t mean you have to leave your brains at the church door.” Reason encourages us to use the brilliant minds God has given us with all their skill in science, research and the exploration of our universe.

|

TraditionAs Anglican Christians, we are inheritors of the ancient Jewish traditions and are part of a living faith that goes back two-thousand years to the early Church, to the Apostles and to Jesus of Nazareth himself. Tradition is the collective experience of those ancient people of faith that we have received in our day. Tradition comes from the Latin verb meaning "to pass from one hand to another”. We cherish and receive from the hands of past Christians the wisdom and customs that evolved from their experiences of the living God.

|